American Catholic Press

16565 S. State Street, South Holland, Illinois 60473

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

by Father Michael Gilligan In some of our churches, hymns and Psalm translations are sung that name God as Yahweh instead of “Lord.” Some of the most popular of these are “Yahweh, I Know You Are Near”, by Dan Schutte, “Yahweh Is My Shepherd” by Millie Rieth, and “Yahweh Is the God of My Salvation” by Gregory Norbet. On the one hand, such liturgical use of Yahweh is an innovation; as far as can be determined, it was never used before in Christian liturgy. On the other hand, the hymns and Psalm translations mentioned are in wide use and well received. They have been effective means of prayer for thousands of people. Here is an example of the effect of one of these songs: The first time I wept at the sound of church singing was at Sunday Mass following the burial of my cousin Mike who at twenty-five, after years of struggle with mental illness, had taken his own life. This was long ago. I don't remember what Sunday it was in the liturgical year or what the readings were, but during Communion everyone sang "Yahweh, the Faithful One." Each time the singing swelled through the refrain, "Yahweh's love will last forever; his faithfulness till the end of time," more tears dropped down my cheeks. This song, and the singing of members of the church who believed its words, filled me with hope and peace.1 In view of such testimony, no one should say "The words of church songs don't matter" or "We don''t think about that." In such a case, too, no one should say, "We don't want to sing during Communion." No, the words of church songs are sometimes more memorable and more influential than the words of Scripture itself, proclaimed in the readings.

As the Second Vatican Council decreed, the words of a church song are of the

greatest importance. In fact,

the first reason why liturgical music matters is not that

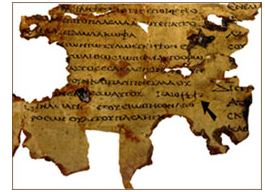

it is aesthetically pleasing, not that it fosters To answer these questions, this article considers the origin and meaning of the divine name Yahweh (or more accurately, YHWH, which is called the “tetragrammaton”3 from the four letters used in the Hebrew), studies the contemporary use of this name, and sets forth arguments in favor of and against its use in liturgy during the proclamation of God’s Word and in songs. At stake here is a question of the liturgical use of terms and concepts that are part of God’s living Word, in the Bible. Is it appropriate for Christians to bring into the liturgy whatever is found in the Bible, anywhere? Should not God's Word be expressed not only in contemporary language but also in terms of contemporary culture? Should not translators and authors take into consideration both Jewish and Christian tradition, as well as the original text? Is not the ongoing faith and practice of the Church a useful norm in both understanding and translating God's word? In this article, these concerns are addressed in three sections: the origin and meaning of the name YHWH, its contemporary use, and critique of its use in the liturgy. I. Origin and Meaning of the Name YHWH To put it in other terms, a biblical name (in a sense) was an alter ego; it represented the person.6 To know someone’s name was to know who and what the person was: not only his or her character or qualities, but especially his or her power, role, or function—what the individual was empowered to do. To be without a name was to be worthless, of no importance. But now they hold me in derision, who are younger in years than I; . . . irresponsible, nameless men, they were driven out of the land. (Job 30: 1, 8) Even in contemporary American English usage, we say that someone feels unimportant because he or she is “only a number,” that is, someone without a name. For someone in biblical times, to know a name for God would be empowering. With knowledge of God’s name, the people could speak to God, pray to God, be in communion with God, and even make claims on God. To bear the name of God was to be possessed by God and to be protected by him. You are in our midst, O Lord; your name we bear. Do not forsake us! (Jeremiah 14:9) People understood the “essence” of God relationally; their first concern was what God did for them, what the relationship was. In a way, their thinking was not “essentialist” but “existential.” Overall, the authors of Exodus and the Psalms, the later editors, and the entire people all invoked the name of God with the same consciousness, the same understanding. The name YHWH comes from God himself; its origin is divine.7 In opposition to the various names of the pagan gods, the God of Israel is “I Am Who I Am,” in one possible rendering. It is in Exodus 3:1-15 that God reveals the divine name. At Mount Horeb, Moses sees a burning bush that is not consumed by its flames. God calls out to Moses by his name; he answers, “Here I am.” God then tells Moses not to come closer, to remove the sandals from his feet, because he is standing on holy ground. Moses is afraid to look at God, so he hides his face. According to the biblical witness, this encounter with God is a moment of awe; reverence is imperative. God then gives Moses a mission to liberate the people of Israel. Moses replies that the people will ask what the name of God is; “What shall I say to them?,” Moses asks. God answers by giving the divine name: Ehveh-Asher-Ehyeh. God says further to Moses what he is to say to the Israelites: “Ehyeh sent me to you. . .This shall be my name forever. This is my appellation for all eternity.”

In Exodus 33:18-20, God clarifies the meaning of the divine name. Moses asks God to let him see God’s glory, God’s presence. Speaking in the first person, God says that he will show Moses all the divine goodness and will proclaim before Moses the name YHWH, as well as the grace that God grants and the compassion that God shows. In other words, God is free to show favor to anyone; he is free to have mercy on anyone. God, then, is a God of love—freely given—as in the writing of John the Evangelist. The “essence” of God, in this context, is as the one who is loving and merciful. We have come to know and believe in the love God has for us. God is love, and he who abides in love abides in God, and God in him. (I John 4:16) In yet another passage, the meaning of the tetragrammaton is clarified. In Exodus 6:2-3 God says that the divine name was not revealed to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. With Moses, the Aramaic YH became YHWH, a symbol of hope and eventual triumph, a name that indicated God was in charge, God was totally free, and God was loving. God also said to Moses, "I am the Lord. As God the Almighty, I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; but my name, LORD, I did not make known to them. (Exodus 6:2-3) Without counting the Book of Ecclesiasticus, the Hebrew Scriptures include YHWH 6,828 times, Elohim (“gods”) 2600 times, Adonai (“Lord”) 439 times, El (“God”) 238 times, and Shaddai (“Almighty”) 48 times.8 Just from sheer usage, we can see that this sacred name, YHWH, is an important part of our history. When did the tetragrammaton originate? The exodus from Egypt took place in the thirteenth century B.C.E. Most modern scholars place it somewhere between 1290-1260; it could be as late as 1224-1216.9 The evidence indicates, then, that the tetragrammaton is ancient, indeed. As is generally acknowledged, the Pentateuch contains elements of retrojection, of later interpretation; other evidence for use of the tetragrammaton at this early date is needed. From about 850 B.C.E., we have a Moabite inscription with a three-letter spelling of God’s name (YHW).10 Use of the name would have predated its written record; the four-letter spelling (YHWH) would have shortly followed. However, all the evidence for such a name before Moses indicates a name without an “H.” Predominant scholarly opinion considers it virtually certain that there was a name for God (such as Yaw) quite apart from the revelation given to Moses.11 One hypothesis is that the earliest strand of the Pentateuch, the so-called "J" tradition, which uses the name Yahweh for God, is the work of a single individual, a woman, who began writing in the later years of King Solomon. According to this hypothesis, the author was part of the court circle, venerating the heroism of David and the order of Solomon: she was not concerned with priests or liturgy. In this hypothesis, the work was completed about 915 B.C. and revised by the "E" ("Elohim") tradition about 850 B.C. In the proposed text of "J," Yahweh is represented in human terms, anthropomorphically, for example, having lunch under a terebinth. In its earliest Israelite usage, Yahweh would have designated a God not unlike the all-too-human gods of the Greeks. Founded on literary analysis, rather than historical-critical study of texts, this hypothesis is useful for drawing attention to what may be the original form of the "J" tradition.12 However, even the tracing of strands of the Pentateuch, "J," "E," and others, is itself an unproven hypothesis. From the viewpoint of some scholars, Yahweh was the name of a dominant god who had a female consort, Asherah, also divine.13 In this perspective, Yahweh is known as a weather god from the hill country of southern Palestine. This cult began in the early part of the first millennium B.C. The archeological data used by these scholars indicate that the term Yahweh had many applications in many Semitic cultures. There was no single, explicit understanding of the meaning of the name itself and no identification with the theology of the revelation given to Moses, recounted in Exodus. While the name Yahweh was widely used in Palestine, the worship of this god underwent considerable consolidation and refinement. Part of the basis for this centuries-long evolution is the Judaic political and social antipathy for Hellenism and local Semitic religions and cultures. The stories of the Exodus and the revelation of Sinai, in this perspective, are religious creations of the Judaic era, to justify elements of the Judaic culture, especially in its self-definition and in its expansion. Since the Bible was extensively edited by Judeans, it does not clarify many aspects of the growing worship of Yahweh. Some developments, however, can be discerned. The earliest evidence indicates that Yahweh was worshipped in both Jerusalem and Samaria but not yet identified with local gods in each town. (See Jeremiah 2:28.) This identification only developed over a long period of time. Another development was in the understanding of the designation Yahweh Sabaoth, originally naming the dominant god of a pantheon. Under Judaic editing, the biblical texts portrayed other heavenly beings as merely "messengers" and "servants" of the supreme god, rather than deities, especially divine stars or planets. The goddess Asherah also disappeared. Monotheism, then, is not the original religious context of the name Yahweh. Another development in understanding Yahweh is the Judaic use of other religious terms for a supreme god, now in a monotheistic context. These include enthronement of God in a special place (on Mount Zion), description of God as a creator and an opponent of chaos, and mention of God as a "sun," reminiscent of a sun-god. (See Psalm 84:12.)14 Similarly, Blenkinsopp thinks that the revelation of the name Yahweh to Moses represents successive stages in the process of interpretation. In other words, the biblical narrative is really a recounting of development of understanding of the name itself.15 In general, then, many scholars agree that long before Moses there was a cult of a god with the same name. So, if the name Yahweh does go back to the time of the Exodus, Moses simply made use of a name that was already in use, to designate the God he knew. It is as though a missionary to the Huron Indians were to tell them that he brings a new revelation of the Great Spirit, Gitchi-Manitou, whom the missionary identifies with the God of the Christians.16 In the came way, Moses would have used the name Yahweh, which was already well known. The point of these hypotheses is that the tetragrammaton should not be considered to be revelation of a divine name without any connection to the human context. The choice of the name Yahweh corresponds to the needs, expectations, and capabilities of the Israelites. At that time, Moses felt compelled to liberate God's people. He had to reflect carefully on the challenge before him. He had to face an empty desert without roads, without water, without clear hope of success. Land that could be inhabited was many miles distant. The Egyptian army would be behind the people in pursuit; the tribes of Canaan would stand before them in resistance. The religion of the common people consisted of eating, drinking, and dancing. Early the next day, the people offered holocausts and brought peace offerings. Then they sat down to eat and drink and rose up to revel. (Exodus 32:6) Moreover, their god was associated with a calf or a steer, a pagan deity; their identity was not firmly established. For the good of the people, the pagan association would have to be broken; a renewal of faith was necessary. The revelation of Exodus 3, then, really concerned God’s own ineffable identity, his own freedom of purpose. This was the God who gave Moses his mission. This explanation of the origin of God’s name does not deny revelation or reduce it to something merely human. It simply assumes that Moses would have used familiar concepts; divine revelation would have been given to him in terms of those concepts. As always, revelation as God’s Word is something given to the mind of a human being. What does the tetragrammaton mean? We cannot be certain. It is even possible that the revelation given to Moses was not of the divine name as such but simply its meaning, its importance. Be that as it may, there are several interpretations that are reasonable; here are three. In the first interpretation, perhaps the most familiar, God is saying, “I Am Who I Am,” that is, “I exist without limit of any kind.” As later philosophers would put it, God’s very nature is to exist—as opposed to the gods of the gentiles, who are nothing. This understanding may be present in the Septuagint, perhaps because of Hellenistic influence at the time of this translation of the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek. While this understanding is valid, it may not be the primary, original meaning of the passage, because the Israelites would not have been directly concerned with “essence” of any kind. Their faith was relational in character. A second interpretation of God�s name might be, �I make to be whatever comes to be.� It could also be translated as �I will bring into being what I will bring into being.� This is a literal translation, says Kruse, of God�s full name.17 In American English this is tautology; it is not, however, in ancient Semitic languages. For example, one could say (as in Exodus 4:13) “Send whomever you want.” That means, “You are free to send anybody; just don’t send me.” In this interpretation, the name is mnemonic in intention. Apart from its literal meaning, a word can have a mnemonic purpose; by its sound, a word is associated with something else. For example, “Babel” is associated with “confusion,” with the word balal. In evaluating a proposal to move the stadium of the Chicago Bears to Gary, Indiana, a commentator recently suggested that the move was to “Scary,” Indiana, alluding to the city’s high crime rate. In both examples, the mnemonic function is evident.

With regard to the name of God, the intent is to stress God’s freedom, especially in creation. In opposition to the origin of the names of the various creatures mentioned in Genesis, whose names are given by Adam as a sign of his dominion, the name of God is not given by Adam or by any human being. God makes the divine name known as an expression of independence of any dominion. Although this second interpretation is valid in itself because God is the creator of everything, a third interpretation may make even more sense. While God’s people needed to hear of the divine freedom and power, they would have been primarily concerned to know what God would do for them, what the relationship would be. John Courtney Murray sees this third interpretation as most valid: “I shall be there as who I am shall I be there.”18 This translation suggests that God would be present to Israel in power, as in Isaiah 52:6: “My people shall know my name; on that day they shall know it is I who says, ‘Here I am.’” By its very enigmatic character, the name God uses as identification suggests awe. In total freedom, God is active, acts again and again, and always acts with fidelity. This is why the name inspires reverence. As in Malachi 3:6, God says, “I am YHWH; I do not change.” By affirming God’s presence among them, the name of God is the banner of God’s people. Moses also built an altar there, which he called Yahweh-nissi; for he said, "The LORD takes in hand his banner; the LORD will war against Amalek through the centuries." (Exodus 17:15)That name is the standard that gives Israel its identity, its destiny, and its unity. On the one hand, YHWH is usually pronounced today by using the spelling and vowels given in Yahweh; and this is perhaps the most accurate way the name was enunciated. The Masoretic vowels have always been missing from YHWH. In later times, the word Adonai was said in place of the tetragrammaton, with its own vowels. In the nineteenth century, through error, the vowels for Adonai were added to the four consonants YHWH, resulting in the inaccurate Jehovah. This artificial term has no basis in Scripture (or in tradition) and, as pure fabrication, it has gradually been eliminated from hymnals and other books. For example, the 1976 edition of the Psalter Hymnal of the Christian Reformed Church includes ten songs that begin with the word Jehovah19 whereas the 1987 edition includes none.20 In accord with a growing ecumenical consensus, the word Jehovah might best be banished from our vocabulary since Yahweh seems to be the most authentic pronunciation we have. On the other hand, this name for God gradually has fallen out of use. Even in the Old Testament itself, Yahweh does not appear in the later books. Out of an ongoing spirit of reverence, the name was used less and less as time went on. In Hebrew, Adonai was used instead; in the Septuagint, the equivalent is Kyrios. At one time, “Yahweh be with you” was an everyday greeting (as in Ruth 2:4). Almost all scholars agree that the tetragrammaton was always pronounced in the priestly blessing, down to the end of the Second Temple period. This blessing was given each day after the morning incense offering; but by the time of Christ, Yahweh was everywhere else pronounced as Adonai.21 Otherwise, utterance of the Hebrew YHWH was restricted to the high priest alone, once a year on the Day of Atonement. He pronounced the name ten times; the priests near him fell prostrate while the other priests sang, “Blest be his name, whose glorious kingdom is forever and ever.” Once, the name was spoken in a loud voice; and its pronunciation was taught to anyone. In time, it was said quietly and taught only to persons considered worthy. After the destruction of the temple, the tradition of the name was carefully preserved but was eventually entirely lost. We have some evidence for the use of the name Yahweh, up to 70 A.D., as in the Misnah, compiled about 300 A.D., in reference to the just mentioned Day of Atonement: And when the priests and the people which stood in the Temple Court heard the expressed Name come forth from the mouth of the High Priest, they used to kneel and bow themselves and fall down on their faces and say, 'Blessed be the name of the glory of his kingdom for ever and ever.' In this text, the "expressed Name" is otherwise translated as "explicit." To say that the Name of God came "forth from the mouth of the High Priest" is thought by some to mean that the Name was pronounced in a whisper. This was mentioned in a memory of childhood by Rabbi Tarphon, who said that even though he struggled to do so, he could not hear the name himself. This testimony is the basis for thinking that at least just before 70 A.D., the Name was said quietly, in this liturgy of the Day of Atonement.22 The ongoing spirit of reverence before God led in time to a decrease even in the use of Adonai in public prayers, then to a decrease even of euphemisms for God (the �Almighty�; the �Place�).23 Today, in some Jewish Orthodox newspapers, one will read instead of “God,” “G-d.” This tradition of awe in the presence of God, of reverence in addressing God, of respect in using any name for God (even a euphemism) is a living tradition from Moses to Christ, to the Gospel of Matthew, to the present. This is what we inaccurately refer to in our translations as “fear of the Lord.” This attitude of prayer—really an attitude of awe and reverence—is a basic and important element of Jewish faith.24 Long before Christ, that attitude demanded virtually complete abandonment of pronunciation of the sacred name of God, Yahweh.

II. Contemporary Use of Yahweh It seems that the use of this term, without precedent in the Christian liturgy, owes its origin to the 1966 Jerusalem Bible, an English version of the French Bible de Jérusalem where the use of Yahweh is maintained in both the current French and English editions.25The use of the Jerusalem Bible at liturgies, especially in lectionaries, would have introduced congregations to the term, especially those who went to Mass during the week.26 Other translations of the Bible have not used Yahweh. The name does not appear in lectionaries or sacramentaries today among Roman Catholic communities in the United States. For example, the new translation of the Psalms from ICEL does not use Yahweh “out of respect for the traditional Jewish reverence for this name.”27As always, Yahweh does not appear in the Sanctus of the Mass. While liturgical sources available to us use sabaoth, the wording is Dominus sabaoth, Kyrios sabaoth, or the equivalent. The current translation in use in the United States is “Lord God of power and might.”28 Aside from some songs, therefore, the name Yahweh does not seem to be used in the liturgy in the United States.

IV. Critique of its Use in Liturgy Some may argue that Yahweh carries with it important meaning, given by God. However, no one knows for certain what that meaning is. All the speculation about the original meaning of Yahweh may be beside the point. Even if we did know the authentic import of the term, the Hebrews may not have understood it in that way. In fact, most etymologies in the Bible are not correct.32 If scholars do not know the original meaning of Yahweh, if the Hebrews may well not have known that meaning, how can people today possibly claim that by using the term they are recovering or restoring something of significance? All the concepts proposed to explain the tetragrammaton are expressed elsewhere in the liturgy, especially in readings from Scripture. Even the current version of the Vulgate, in quoting the Canticle of Moses in Exodus 15:3, does not say “Yahweh is his name.” It is Dominus quasi vir pugnator; Dominus nomen eius!”33

Others may argue that using Yahweh is a good way to stress our Jewish origins and our bond with Jews today. Our origins, however, are in Judaism at the time of Christ, not centuries before. Moreover, use of the name Yahweh does not bind us to Jews; it alienates them. Our Jewish origins are emphasized in many ways already, especially in the use of an Old Testament reading and a Psalm, in most celebrations of the Sunday Eucharist. Some may argue that songs using Yahweh are familiar and that altering the text would be difficult for some people. In some cases, the copyright holders are not willing to permit alteration. Dropping the songs would constitute a loss for liturgy. This line of reasoning would have some force, were it not for the many sound and cogent arguments against the use of Yahweh. Today, sensitivity toward Jewish people demands that we respect their own feelings and traditions as a living community of faith, not simply as an old religion from which the Church came. Christians should acknowledge “Judaism as a living tradition that has had a strong and creative religious life through the centuries since the birth of Christianity.”34 Moreover, Christians should respect “the continuing validity of God’s covenant with the Jewish people and their responsive faithfulness, despite centuries of suffering, to the divine call that is theirs.”35As Pope John Paul II puts it, Jewish and Christian believers must come to know each other more thoroughly. We must do so, not just because we coexist in the same place, but also because we are so closely bound together. Christians, says the Pope, must try to know “as exactly as possible” the distinctive beliefs, religious practices, and spiritual life of the Jewish people.36 The current Pope, Benedict XVI, follows the same line of thought. He says that God's people were wholly correct in declining to speak the name YHWH, because such a practice would bring God's identity down to the level of pagan gods. By the same token, says Pope Benedict, recent Bible translations, such as the Jerusalem Bible, were mistaken to spell out this name, as though it were like any other name. The people of Israel always regarded this name as "mysterious and unutterable." Some Bible translations, however, have pulled the divine mystery of identity down to something familiar, in a common tradition of pagan religions. In contrast, says the Pope, God's name brings us into a special relationship with him. Without qualification, God simply exists. That means he is always there for human beings, yesterday, today, and tomorrow. In Isaiah, God says, more clearly, "I am he." This is a more emphatic statement of God's name.37 The same point is made by Gerard Sloyan. Joseph Gelineau, S.J., he says, is named as the primary translator of the Psalms in the Jerusalem Bible. Sloyan says that Gelineau's translation "did a serious disservice to Catholics worldwide" by giving us Jahveh rather than Seigneur for YHWH. However, Jews at the time of Christ and to the present say instead Adonai or HaShem ("Lord" or "the Name"), both in public reading and in speaking. Therefore, says Sloyan, it is not prudent to invite Jewish friends to Catholic liturgies if they are going to hear the name of God aloud. "This is an offense to their pious ears, and so should it be to Christians."38 He says that "Yahweh-and-me " lyrics that replace "Jesus-and-me" hymns are no great improvement. In such songs, the biblical paraphrases are deprived of all public character; they have become private prayer, in contradiction to the spirit of the liturgy, says Sloyan.39 Finally, Sloyan says that "Yahweh is the God of my salvation" is both “offensive to the pious Jewish ear and is scarcely recognizable” as a Psalm.40 One direct prohibition of the use of Yahweh is that found in the Ecumenical Guidelines of the Ecclesiastical Province of Chicago. This document says explicitly: “Even apart from services with the Jews, the public use of the name of the Lord in Hebrew (YHWH) should be avoided.”41 While not normative legislation for the whole United States, this is church law for Catholics of the State of Illinois. As Balthasar Fischer puts it, Psalms in the liturgy must never address or speak of God as Yahweh. This is so because “the pronunciation of this most holy Hebrew name violates the deepest religious feelings of our Jewish brothers and sisters.”42 Roy Rosenberg points out that Yahweh is too sacred a word ever to be used by Jews. The Jewish Orthodox do not even substitute Adonai; they use HaShem (“the name”) in ordinary speech.43 The editors of The Catholic Study Bible acknowledge this practice of avoiding use of Yahweh. With understatement, these editors say that “the modern translator and commentator will have to make a decision on whether to try to respect this understandable religious sensitivity.”44 Gail Ramshaw says that using Yahweh “wholly disregards the religious sensitivities of pious Jews who deem spelling and pronouncing the divine name blasphemous.” She says that it is "shocking" that one generation after the Holocaust,"Western Christians could adopt a religious practice with apparently no concern for its religious offense to Jews."45 In general, then, for reasons of charity alone—love for our Jewish friends who worship the same God—we should not use Yahweh in the liturgy. Furthermore, as many authors have pointed out, the New Testament uses Kyrios and Dominus with reference to Christ. With the use of Yahweh comes a loss of a Christian and Christological interpretation of the term. Fischer, for one, says that such usage destroys the bridge to any such interpretation, “a bridge which Providence built before Christ, when the Greek Septuagint translated the Hebrew name for God by Kyrios.46 Ramshaw expresses the same judgment.47 Even more important is the pastoral reception of the term Yahweh. To many people, says Fischer, it sounds like another deity, perhaps a fourth divine person, in addition to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.48 The same point is made by James Barr, who thinks that the use of Yahweh is wrong. After arguing that he has become sensitive to Jews because he lived among them and that he doubts the name Yahweh is appropriate for later books of the Old Testament (such as Ezra or Daniel), he brings up this third and most important argument. The use of Yahweh, he says, may lead people to infer that reference is being made, not to the true God but to some other being, "a barbaric ancient tribal deity with an outlandish personal name of his own." 49 How can ordinary Christians make the term Yahweh a natural expression of prayer, when it is found neither in private piety nor in official liturgy? As the Roman Instruction on the Translation of Liturgical Texts says, whatever vocabulary we select should be in common usage, suited to the majority of the people who speak it every day, including “children and those who are not well educated.”50 There is, therefore, a serious psychological difficulty in using the term Yahweh. It is not in common usage and may be misleading.

Another argument against use of the term Yahweh is that Christians explicitly model their prayer on that of Christ. He is both our intercessor with the Father and our teacher of prayer. We say the Our Father, because that is the pattern of prayer Christ gave us. We wish to pray as he prayed, to trust in the Father as he did, to take part in his own sentiments and thoughts as much as possible. This is one reason why the Gospel of John includes so much prayer attributed to Christ; that is the way we too should pray. Moreover, Jesus Christ never used Yahweh in his prayer, never taught his disciples to use this term, never would have conceived of using it. In fact, Jesus Christ and his disciples would have been shocked and scandalized by any use of Yahweh. The term had been out of common usage for three hundred years and was excluded from usage by the traditions that the Messiah said he had come to uphold.51 Christians, then, should follow the example and teaching of the one they acknowledge as their Messiah. A final argument against the use of Yahweh in the liturgy is, in a way, most critical. Hymns and Psalms used in the liturgy must harmonize with it, support it, and be in the same spirit. Neither the current lectionaries nor sacramentaries in the United States use the term Yahweh. Since this is so, the idiom of the liturgical books is in direct conflict with such hymns as �Yahweh, I Know You Are Near.� It is not the liturgical books that need to change; it is the texts of some of our hymns and Psalm translations. For sound pastoral reasons, these songs must either be altered or omitted. In 1996, when this article was first published, the hope was expressed that the Ecumenical Guidelines of the Province of Chicago would, in this respect, be applied to the whole country. This hope has now been fulfilled. In 2001, the instruction Liturgiam Authenticam directed that, in accord "with immemorial tradition," the tetragammaton was to be translated into the equivalent vernacular word.52 On June 29, 2008, by directive of the Pope, the Congregation for Divine Worship ordered that the tetragrammaton never be used in the liturgy, that liturgical translations should exclude the term, and that "Lord God" should be used for Adonai Yahweh, as in the Sanctus. 53 Roma locuta est; causa finita est. In sum, there is no Catholic doctrine that God is to be addressed

as Yahweh. In fact, there is a constant tradition that God

is not to be addressed as Yahweh but as “Father,” as

well as by other names. The term Yahweh is improperly derived

from scriptural sources and not at all from liturgical sources. Therefore,

by the criteria of the Second Vatican Council, this term should have

no place in our liturgy. References 1. Kathleen Harmon, “Music Notes,” Liturgical Ministry 16 (Spring, 2007) 108. 2.Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1963) 112, 121. 3. Frederick Matthewson Denny, "Names and

Naming,"

The Encyclopedia of Religion, ed. Lindsay Jones et

al. (New

York: Macmillan, 2005) 9, 6406-6412; "God, Names of," The

New Standard Jewish Encyclopedia, ed. Geoffrey Wigder et

al., 7th ed. (New York: Facts on File, 1992) 373; Louis F. Hartman

and S. David Sperling,

"God, Names of," Encyclopedia Judaica (Detroit:

Thomson Fale, 2007) 7, 672-676; "The Hebrew Name for God-YHVH," www.hebrew4christians.com/Names_of_G-d/YHVH/yhvh.html;

Heinz Kruze, S.J., "Der Wunderbare Name: Zur Herkunft and Sinngehalt

des Jahwe-Namens," ZKT 112 (1990) 385-405; “Tetragrammaton,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tetragrammaton; www.yahweh.org/PDF_index1.html. 5. John Courtney Murray, S.J., The Problem

of

God (New Haven: Yale University

Press, 1964) 8. Kruse, “Der Wunderbare Name,” 387. 12. Harold Bloom, The Book of J (New York: Vintage Books, 1991). 13. Of the considerable literature on early Israelite religion, some works may be esp. useful: William F. Albright, Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1990): Jon Day, Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000): Saul M. Olyan, Asherah and the Cult of Yahweh in Israel (Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press, 1988): Mark S. Smith, The early History of God (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 2002): Johanna H. Stuckey, “Goddess in the Spotlight: Asherah and the God of the Early Israelites,” http://www.matrifocus.com/LAM04/spotlight.htm. 14. This scholarly perspective is found, for example, in The Triumph of Elohim: from Yahwisms to Judaisms, ed. Diana Viakander Edelman (Kampen, The Netherlands: Pharos, 1996). See esp. Herbert Niehr, "The Rise of YHWH in Judahite and Israelite Religion: Methodological and Religio-Historical Aspects," 45-72. 15. Blenkinsopp, Joseph, The Pentateuch (New

York: Doubleday, 1992) 149. 17. Kruse, “Der Wunderbare Name,” 396.

Cf. John Bright, A History of Israel, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia:

Westminster, 1972) 151-153. The composer of “Yahweh, I Know You Are Near” recently

admitted his reliance on the Jerusalem Bible. He says that he "wrote

this piece in 1970, as a very young man. . .I first learned to pray

the Psalms from the Jerusalem Bible. . . I turned to the JB translation

in considering 28. For a history of the Sanctus, see

Bryan D. Spinks, The

Sanctus in the Eucharistic Prayer(Cambridge: University

Press, 1991). None of the

Sanctus texts cited by Spinks uses Yahweh. 30. Raymond E. Brown, S.S., The Critical Meaning of the Bible (New York: Paulist Press, 1981). 31. Albert

Gélin, “Yahweh ou

Seigneur?,” L’Ami

du Clergé 69 (1959) 333-34 . 33. “The Lord fights like

a man! ‘Lord’ is his name!,” Nova Vulgata Bibliorum

Sacrorum Editio, rev. typical ed. (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice,

1986) 103. (This wording represents a correction from the previous

edition: Iahveh nomen eius!) 38. Gerard Sloyan, "Some Thoughts on Bible Translation," Worship 75 (2001) 236. 39. Idem, "Some Thoughts

on Liturgical Preaching," Worship 71

(1997) 338. 43. Roy A. Rosenberg, The Concise Guide to Judaism (New York: Penguin, 1990) 12. 44. The Catholic Study Bible, ed. Donald Senior, C.P. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990) 6-7. 45. Gail Ramshaw, God Beyond Gender (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995) 52-53. 46. Fischer, “Christological Interpretation,” 229. 47. Ramshaw, God Beyond Gender, 53. 48. Fischer, “Christological Interpretation,” 229. 49. James Barr, “Biblical Translation and the Church,” New Blackfriars 49 (1968) 285-92; here, 288. 50. Consilium, Instruction on Translation of Liturgical Texts (Washington, D.C.: NCCB, 1969) l5. 51. Matthew 5:17.19: “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law and the prophets. I have come, not to abolish them, but to fulfill them...” 52. Congregation for Divine Worship, Liturgiam Authenticam (Washington, D.C.: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2001) 74-75. 53. Cardinal Francis Arinze, Letter to the Bishops' Conferences “On the Name of God” (June 29, 2008).

|

||||||||||||||||||||

participation,

not that it highlights important parts of the liturgy, not that it is good art,

and not that it provides a good human experience. The Council teaches that the

reason why music is important is that it is joined to the words, which are themselves

sacred. These texts, says the Council, should be in conformity with Catholic

doctrine and should primarily be derived from Scripture and from liturgical sources.

participation,

not that it highlights important parts of the liturgy, not that it is good art,

and not that it provides a good human experience. The Council teaches that the

reason why music is important is that it is joined to the words, which are themselves

sacred. These texts, says the Council, should be in conformity with Catholic

doctrine and should primarily be derived from Scripture and from liturgical sources.