by Father Michael Gilligan

The Second Vatican Council:

Doctrine, Bible, and Liturgy

In the Catholic Church, great authority is given to an ecumenical council, a

gathering of her bishops from all over the world. The Pope himself presides over

such a gathering, either in person or through a representative. Of the various

documents such a council might give us, a constitution would be especially important;

it would be a statement of principles, a blueprint for renewal. In 1963, such

a document was approved by the Second Vatican Council: the Constitution on the

Liturgy.

In that document (#121), the Council fathers gave some norms for

the texts of hymns used in the liturgy. These texts, they said, should

be in conformity with Catholic doctrine and should be drawn primarily

from the Bible and from the “sources” of

the liturgy, the earliest documented records.

What is the Catholic doctrine of the Church today? “Catholic

doctrine” refers

not only to official dogmas, carefully defined,

but also to teachings

that are commonly acknowledged as true. Since 1963, almost all the

changes in doctrine are not in

terms of orthodoxy or heresy, right

or wrong, true or false. By and large, the documents of the Council

give us changes in emphasis, in theological method, and in ways of

thinking. Since the texts of hymns are to reflect this Catholic doctrine,

these texts will have the same kind of emphasis, the same theological

method, and the same ways of thinking. It will be a case, not

of

condemning the past, but of going to something better. As Pope John

XXIII put it, it is an aggiornamento, a gradual

updating, rather than a revolution. So, by studying theology and

the history of Church doctrine, musicians will be able to choose

good hymns. Without that knowledge, they will not.

The

Council said that the texts of hymns are to be drawn from the Bible.

Like Catholic doctrine, the teaching of the Bible is only well understood

with the help of theology and history. Bible texts should be interpreted

accurately; it is not just a question of quoting verses or phrases.

Allowance has to be made for the gradual development of certain Biblical

teachings. A given hymn, for example, does not have to express all

that needs to be said about a certain belief. In fact, it may well

be appropriate for a text to treat only one aspect of faith, and

even that according to only one aspect of revelation. Certainly,

however, it is good for hymn texts to use the idiom of Scripture

as Catholics know it. In hymns, for example, it is a help

to prayer to see God spoken of as “Father,” rather than “Yahweh.” It

is good to hear phrases from the Psalms in our hymns. It is good

to see Christ represented in our hymns as our mediator with the Father,

as the one through whom we pray. Finally, the Council said that hymn texts should primarily be derived

from the sources of the liturgy. Like the Bible, these sources are

well understood only through study. Musicians, reviewers, parish

priests, and all involved in choosing hymns need to be familiar with

such sources as the Apostolic Constitutions, the Didaché, the Didascalia, the

writings of St. Justin, and the early sacramentaries, as well as

their history and theology. It is not sufficient merely to cite these

sources; one has to understand them and use them rightly. Every pastoral

musician who chooses hymn texts needs to know why and how the sources

of the liturgy affect the choice of hymns.

The

Council said that the texts of hymns are to be drawn from the Bible.

Like Catholic doctrine, the teaching of the Bible is only well understood

with the help of theology and history. Bible texts should be interpreted

accurately; it is not just a question of quoting verses or phrases.

Allowance has to be made for the gradual development of certain Biblical

teachings. A given hymn, for example, does not have to express all

that needs to be said about a certain belief. In fact, it may well

be appropriate for a text to treat only one aspect of faith, and

even that according to only one aspect of revelation. Certainly,

however, it is good for hymn texts to use the idiom of Scripture

as Catholics know it. In hymns, for example, it is a help

to prayer to see God spoken of as “Father,” rather than “Yahweh.” It

is good to hear phrases from the Psalms in our hymns. It is good

to see Christ represented in our hymns as our mediator with the Father,

as the one through whom we pray. Finally, the Council said that hymn texts should primarily be derived

from the sources of the liturgy. Like the Bible, these sources are

well understood only through study. Musicians, reviewers, parish

priests, and all involved in choosing hymns need to be familiar with

such sources as the Apostolic Constitutions, the Didaché, the Didascalia, the

writings of St. Justin, and the early sacramentaries, as well as

their history and theology. It is not sufficient merely to cite these

sources; one has to understand them and use them rightly. Every pastoral

musician who chooses hymn texts needs to know why and how the sources

of the liturgy affect the choice of hymns.

What is most important in hymn texts?

Many principles affect hymn texts; there are all kinds of legitimate concerns.

Some people want texts that include both men and women. Some people want texts

that are familiar. Some people want texts that are poetic and beautiful. Some

want texts that are clear and contemporary. Some want to avoid archaic language.

They want the kind of English found in the Lectionary and the Sacramentary, not

the idiom of 18th and 19th century England. Although not every hymn will please

everyone, such

needs have been taken into consideration in this hymnbook. Each parish has available

to it the choice that is necessary.

But for Catholics, the important principles affecting hymns are the needs of

the faith, the principles of the liturgical renewal. The main ideas that influence

our texts are those that come from the Church herself, not the wider culture.

Renewal of hymnody is a question of discovering our own roots, our own origins

in faith, our most essential and central beliefs.

At the beginning of this article, we reviewed the teaching

of the Second Vatican Council: the texts of hymns should agree with

Catholic doctrine. These texts will have the same kind of emphasis,

the same theological method, and the same ways of thinking. Ultimately,

renewal of hymnody is a question of discovering our own roots, our

own origins in faith, our most essential and central beliefs. Here,

then, are some of the principles that form the basis for the hymn

texts found in the Leaflet Missal. There are three important

areas in which major shifts have occurred in liturgical theology:

the Trinity, the role of Christ in prayer, and the role of the Spirit.

The Trinity: A Dynamic Relationship

With regard to the Trinity, the documents of the Vatican Council regularly use

the idiom of Scripture and early tradition: we pray to the Father, through the

Son, in the Spirit. As the great 20th century theologian, Karl Rahner, S.J.,

pointed out, the Trinity in the work of salvation and the Trinity who dwells

in our hearts is the same reality, the same God. So, we need to see ourselves

as sons and daughters in the Son, united in the Spirit. In the liturgy, the Trinity

is not an external reality but something immanent, present in our hearts by grace.

God himself dwells within us in the person of his Spirit.

Many Christians need a richer understanding of their faith in the Trinity. Some

think of God as three separate, individual beings, more or less a divine “committee.” Some

see God simply as one, without differentiation. People need to celebrate in the

liturgy the fullness of their faith. This theology is important not only in our

prayer, especially our hymns, but also in the very way in which we experience

God’s grace. God’s love

is made known to us through the Son, through the mediation of a Word that itself

is a personal experience for us of divinity and transcendence. That love is also

made known in the Spirit, in the community of the Church, the gathered congregation.

Implicitly and experientially, we share the life of God within the family, within

the household of the faith, within the unity of the Spirit.

Trinity and Liturgy

There are three significant ways in which the theology of the Trinity affects

the liturgy: in the reform of the Mass, in the wording of the doxology (Glory

to the Father...), and in the wording of our hymn texts.

In the 1969 Order of Mass, two prayers to the Trinity were omitted: Accept,

Holy Trinity, during the preparation of the gifts, and May it please

you, Holy Trinity, at the end of Mass.

In this reform, the traditional orientation of prayer to the Father was more

fully restored. We do not pray to the Trinity as such, but to God. We pray to

him through the Son, in the Spirit. This perspective was always present in the

Roman Canon and its prefaces, as well as almost all the public prayers of the

priest.

The ancient form of the doxology was worded in exactly this way: through the

Son, in the Spirit. A change was needed in the fourth century, because of the

violent, prolonged struggle against the Arian heretics, who denied the divinity

of Christ At that time, people began to use another form of doxology:

to the Son and to the Spirit. Through exhaustive study, the liturgical scholar

Joseph Jungmann, S.J., showed that the liturgy was substantially distorted, in

its reaction to heresy. Now that the danger is long past, he says, the Church

can return to the original perspective of the sources of the liturgy. Especially

in the liturgy of the hours, in morning and evening prayer, the ancient tradition

should be restored. As in the Eucharistic Prayer at Mass, we give God glory through

the Son, in the Spirit.

By the same token, hymns about the Trinity should reflect the tradition of the

ancient, undivided Church. Hymns that are directed to the Trinity as such or

to each person successively should not be used, no matter how familiar they may

be; they are not in accord with the spirit of the liturgy. Instead, all Trinitarian

hymns should truly accord with the nature of the Eucharist, morning and evening

prayer, and the sacraments.

Jesus Christ: Our Mediator with God

With regard to Jesus Christ, many Catholics still see him one-sidedly

in his divinity, as the eternal Son of God. Yet, by and large,

the liturgy rescinds from his divinity. Instead, both Scripture

and early tradition emphasize the humanity of Jesus Christ. In

fact, he is our mediator with the Father precisely in his humanity.

This is why we pray in the Mass through Christ our Lord.

The liturgy is not so much prayer to Christ as it is the prayer

of Christ.

This is how Jesus taught us to pray: to his Father, through him.

This is how the Bible and the sources of the liturgy teach us to

pray. This is how the Church herself has always prayed, in the Eucharistic

Prayer, age after age. This way of thinking helps us understand the

Resurrection as part of the whole mystery of Easter, the Passover

of the man Jesus to glory with the Father. In some hymns in the past,

the Resurrection and other miracles were thought of as evidence of

the divinity of Christ. Yet the disciples themselves did not have

this understanding! Instead, the Bible and the sources of the liturgy

teach us that the Resurrection is a victory for Jesus in his humanity

and therefore in our humanity. Because he is risen, we too will rise.

Because he could conquer, we too will conquer. Because he is Lord,

we too will come to glory.

Similarly, in this theology, we can understand better how Jesus

is a priest for us. In some

hymns,

Similarly, in this theology, we can understand better how Jesus

is a priest for us. In some

hymns,

he was once described as a sacred

person to be worshipped, to be our benefactor,

to consecrate the

bread and wine, to descend among us. Instead, as a priest, Jesus

is understood

in the sources of the liturgy to be primarily a mediator,

an intercessor before God. As in

the Epistle to the Hebrews, Jesus

prays on our behalf and helps us to pray;

we pray to God through

him. The priesthood of Christ has taken the place of all the

priests

who came before him:

Under the old covenant, there were many of those other

priests, because they died and could not continue their work. But

Jesus lives on forever, and his .work as priest does not pass on

to someone else. And so he is able, now and always, to save those

who come to God through him, because he lives forever to plead

for them. Jesus, then, is the High Priest that meets our needs.

(Hebrews 7:23-26)

This is not an isolated paragraph, taken out of context;

it is the main point of the whole Epistle to the Hebrews. The priesthood

of Christ is not so much the descent of God among us as it is the

prayer and offering of Christ, bringing us to God. It is an upwards

movement, directed to heaven: This is why the liturgy does not emphasize

adoration of Christ; instead, it is to God the liturgy directs our

prayers, our offering, and our adoration. The liturgy is not so much

prayer to Christ as it is the prayer of Christ. Our hymns, then,

should express this theology. Because Christ is our mediator, we

need many Easter hymns. They will be sung for eight Sundays, up to

and including Pentecost, the last Sunday of Easter. The celebration

lasts, not for one day or one week, but for 50 days. In fact, some

Easter hymns will be appropriate in any season, because every Sunday

celebrates the death and Resurrection of Christ. Jesus is Lord, all

during the year.

Again, because of the role of Christ, we need many hymns about

the Second Coming. This theme of the liturgy is not limited to

Advent; it is also found especially in the month of November. To

pray for the return of Christ is to pray for the fulfillment of

his victory, for the completion of the mystery of Easter. “Christ

has died, Christ is risen, Christ will come again.”

The Church in Our Hymns

There is another theme that is needed in our hymns:

the reality of the Church as God’s People. This teaching has many dimensions,

among them, the universal call to holiness, the Church as God’s

creation (that is, the Body of Christ, the People of the Covenant,

and God’s vineyard), the Church as a Servant, the Church as a

sign of the kingdom, and the Church as a Mother, like Mary. We find

these images in the Bible, in both the Old Testament and the New. Again

and again, we use these images in liturgy. God’s Word determines

the way we pray, the theology and language of our prayer. So, the

hymns we sing should reflect the great themes of the Bible. When

we sing of the Church, we express what we believe about her, in

all the fullness of our faith.

The Universal Call of God

There are many misconceptions about the nature of the Church.

Perhaps one of the greatest is that found in the media. It is often

the case that movies and television identify the Church with the

clergy and with people in religious orders, that is, monks, nuns,

brothers, and sisters. When someone on television is portrayed as

leaving religious life, becoming a lay person again, that person

is said to be “leaving the Church,” as though lay people do not belong

to the Church.

For centuries, many lay people felt that they were less a part of the Church

than priests or nuns. Celibacy, in particular, was thought to be a means of being

a “first-class” member. In part, such a feeling was a cultural tendency,

a world-view. In some ways, however, that feeling was based in fact.

Hand missals in vernacular languages were once condemned by bishops, because

lay people were not considered worthy to read the sacred text. Catholic school

children of Eastern Rite priests suffered discrimination, because their fathers

were married. Male choirs were considered preferable to mixed choirs. And when

women were permitted to take on the role of lector, they were required to read

outside the sanctuary, forbidden to read from the pulpit.

In opposition to this kind of thinking, the Second Vatican Council stresses unequivocally

the traditional doctrine that there is one, universal call to holiness. All the

baptized, whatever their state in life, are equally called to be holy. So, in

our hymns about the Church, it is appropriate to use the Scriptural idiom in

which all the baptized are spoken of as “saints.” It is appropriate

to use the powerful theology of baptism, by which all members of the Church are

saved through water and faith. It is appropriate to sing of the leaders of the

Church as servants and members of the Church, not as individuals endowed with

greater grace than other baptized people. Above all, it is appropriate to sing

of the Church as God’s People, as one family of faith. Baptism is more

important than any distinction of class or culture, race or nation, rite or language,

age or sex.

The universal call of all nations and races is found, for example, in such hymns

as “From All Who Dwell,” “Just as the Grain,” and “Where

Love Is Living.” The universal call of all the baptized is found in “Come,

You Faithful” and “Father, Make Us One.”

The Church as God’s Creation

There is another common misunderstanding of the concept of the Church.

In the United States, people are said to attend the “church

of their choice.” Many Americans think of their membership

as the result of personal preference. They consider faith as primarily

an individual gift, prior to the liturgy, apart from the Church.

They think that faith is found in the individual’s personal

acceptance of Christ, in the individual’s free choice, in

the individual’s private decision. What is really important,

say many Americans, is doing good, following your conscience, and

tolerating your neighbor. After all, that neighbor may have religious

preferences that are different from your own. Religion is essentially

a private matter, a question of individual choice. The Church,

such people say, is primarily a gathering of individuals who come

together to express in common their religious traditions and to

strengthen their faith.

In contrast to this viewpoint, the Vatican Council emphasizes the

ancient understanding of the Church as God’s creation. People

who belong to the Church do so not because of their choice but because

of God’s. For this reason, babies—without mature faith—are

baptized. For this reason, imperfect people and even sinners remain

members of the Church. There will be bad people who are part of the

Church and good people who are not. The classic statement of this

perspective is that salvation is by faith, not human deeds. And that

faith is found and expressed in the Church. Faith comes from the

liturgy itself, not beforehand; faith comes from sharing in the life

of the Church, from something we do in common.

Our hymns sing of God’s People crossing the Red Sea (“Come,

You Faithful”), the desert (“Give Thanks to God, for

God is Good”), or the Jordan River (“Dayenu”).

When we sing these hymns, we think of the Church. God’s People

from their beginning were chosen, singled out, and favored by God

directly. The meaning of the Exodus is that God intervened in history,

on behalf of his chosen faithful. The history of God’s People

is the history of the Church. Our hymns, then, should call to mind

our Jewish origins, our biblical roots, and our long struggle to

follow God, down through the ages.

Good hymns about the Church will

be more Hebrew than Roman, more universal than Latin, more involved

with God's great deeds than our own wants and desires. It in not

that we have chosen him but that he has chosen us. What counts is

God's choice, not ours; God's decision, not our preference; God's

grace, not our sin.

We celebrate this teaching, about the Church as God's creation,

when our hymns describe the Church as the Body of Christ, a living,

organic union with Christ himself, as in "See Us, Lord, around Your

Altar" and "To Christ the King." We sing of the Church as God's Chosen

People, as in "The Church's One Foundation" and "The Lord of Light

Is Near." We sing of the Church as the result of God's Covenant,

as in "How Great and Good Is He" and "The Bread We Hold in Our Hands."

We sing of the Church as gathered by God, formed by his will, as

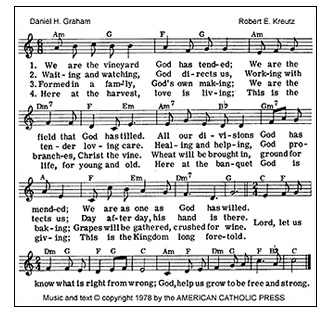

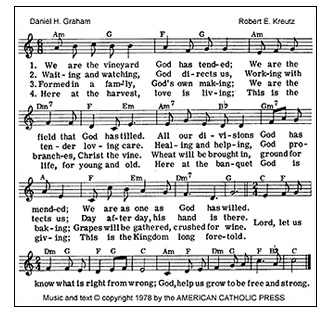

in "Shepherd of Life." Finally, we sing of the Church as a vineyard,

a garden that God himself has planted and nourished, as in "We Are

the Vineyard."

The Servant-Church

There is another theology of the Church, which has today been largely abandoned.

In recent generations, people spoke of the Church as a “perfect society,” like

the State with all it needs to endure.

People

acknowledged that individuals sinned, even individual Church leaders.

But the Church herself was seen as the New Jerusalem, perfect and

blameless, strongly identified with the Bride of Christ (or with

Christ himself). No matter how serious sin might be, it was not attributed

to the Church as such. Seeing the Church as she will be in heaven

is a legitimate theme of the liturgy, as in “Jerusalem,

My Happy Home.” That theme, however, refers to the end of time,

not the present; it needs to be balanced by other, equally important,

themes.

In the doctrine of the Vatican Council, certain Scriptural themes

are brought to the fore, to help us understand the Church more accurately.

The Church is described as a “pilgrim Church,” a people who are “on the

way,” who have not yet arrived at their destination, as in the hymn, “On

Our Journey Home.” The Church is also described as a “Servant Church,” following

the example of her Lord, as in the “Ecumenical Hymn to God,” where

the Church is said to ‘serve and guide.”

According to this teaching, the Church serves the whole community,

in fact, the whole world, by promoting whatever is authentically

human, just, and equitable. Although her members take pride in her,

as in “God’s Plan Is Crystal

Clear,” the Church does not rule; she serves.

The Church as A Sign of the Kingdom

There is yet another false viewpoint, primarily secular in its origins,

that sees the Church as something like a giant corporation, existing

for her own benefit or perhaps for the benefit of her members. From

this viewpoint, often represented in the media, the Pope is portrayed

as someone who runs the Church, issuing moral edicts now and again,

so that he retains control over the masses and keeps the organization

strong.Yet the Church is not a corporation. Her origins

are in God; her destiny is divine. Through her celibate monks and

nuns, through her humility and service, through her poverty and charity,

the Church is a sign of God’s kingdom. She knows that the reign of God is

near; to that future, she bears witness. She works for the liberation

of the oppressed, the relief of the anguished, and the salvation of

the poor. By her sacrifices in the present, the Church testifies that

what is to come has eternal value. This theme is found in many Advent

songs, such as “Give the King” and “Rise Up, 0

Lord Our God.”

The Church as A Mother

Here is one last observation. In recent .generations, some spoke

of the Church as a Mother who “knows best,” who corrects

and reproves. At that time, Church leaders emphasized authority

and obedience. Today, we return to the teaching of the Fathers

of the Church. If we sing of her as a Mother, we do so because

the Church is the source of our life. She brings us to birth, she

nourishes us, and she watches over us. Hymns about Mary, the Mother

of Christ, will naturally be associated with the Church, as in “Immaculate

Mary” and “Sing of Mary.” The association is

Scriptural and patristic.

Conclusion

These then, are the themes that should predominate in hymns about

the Church. Just as there are new theological emphases in our prayers

about God, Christ, and the Spirit, so too the Church is understood

in a new way, whenever we sing in the liturgy. The Church is God’s

People, with all the rich meaning found in that concept.

The

Council said that the texts of hymns are to be drawn from the Bible.

Like Catholic doctrine, the teaching of the Bible is only well understood

with the help of theology and history. Bible texts should be interpreted

accurately; it is not just a question of quoting verses or phrases.

Allowance has to be made for the gradual development of certain Biblical

teachings. A given hymn, for example, does not have to express all

that needs to be said about a certain belief. In fact, it may well

be appropriate for a text to treat only one aspect of faith, and

even that according to only one aspect of revelation. Certainly,

however, it is good for hymn texts to use the idiom of Scripture

as Catholics know it. In hymns, for example, it is a help

to prayer to see God spoken of as “Father,” rather than “Yahweh.” It

is good to hear phrases from the Psalms in our hymns. It is good

to see Christ represented in our hymns as our mediator with the Father,

as the one through whom we pray. Finally, the Council said that hymn texts should primarily be derived

from the sources of the liturgy. Like the Bible, these sources are

well understood only through study. Musicians, reviewers, parish

priests, and all involved in choosing hymns need to be familiar with

such sources as the Apostolic Constitutions, the Didaché, the Didascalia, the

writings of St. Justin, and the early sacramentaries, as well as

their history and theology. It is not sufficient merely to cite these

sources; one has to understand them and use them rightly. Every pastoral

musician who chooses hymn texts needs to know why and how the sources

of the liturgy affect the choice of hymns.

The

Council said that the texts of hymns are to be drawn from the Bible.

Like Catholic doctrine, the teaching of the Bible is only well understood

with the help of theology and history. Bible texts should be interpreted

accurately; it is not just a question of quoting verses or phrases.

Allowance has to be made for the gradual development of certain Biblical

teachings. A given hymn, for example, does not have to express all

that needs to be said about a certain belief. In fact, it may well

be appropriate for a text to treat only one aspect of faith, and

even that according to only one aspect of revelation. Certainly,

however, it is good for hymn texts to use the idiom of Scripture

as Catholics know it. In hymns, for example, it is a help

to prayer to see God spoken of as “Father,” rather than “Yahweh.” It

is good to hear phrases from the Psalms in our hymns. It is good

to see Christ represented in our hymns as our mediator with the Father,

as the one through whom we pray. Finally, the Council said that hymn texts should primarily be derived

from the sources of the liturgy. Like the Bible, these sources are

well understood only through study. Musicians, reviewers, parish

priests, and all involved in choosing hymns need to be familiar with

such sources as the Apostolic Constitutions, the Didaché, the Didascalia, the

writings of St. Justin, and the early sacramentaries, as well as

their history and theology. It is not sufficient merely to cite these

sources; one has to understand them and use them rightly. Every pastoral

musician who chooses hymn texts needs to know why and how the sources

of the liturgy affect the choice of hymns.  Similarly, in this theology, we can understand better how Jesus

is a priest for us. In some

hymns,

Similarly, in this theology, we can understand better how Jesus

is a priest for us. In some

hymns,